New Koinobori Print! Celebrating Childhood, Spring, Strength and Perseverance

The leaves are budding. The flowers are blooming. The sweet essence of spring is finally in the air. Japan is in the middle of its sakura flower-viewing season, Hanami (花見), and soon after that is the Golden Week (ゴールデンウィーク) or 黄金週間 (ougon shuukan) named for the four consecutive holidays falling on the first week of May. The May 5th Children's Day falls as the last of the holidays in the Golden Week holiday chain and is perhaps the most significant one. For nothing screams the height of spring and the forthcoming week-long celebration as seeing its giant colourful carp streamers swimming in the wind against the bright turquoise sky, amongst the gently billowing blush sakura petals as confetti descending from above.

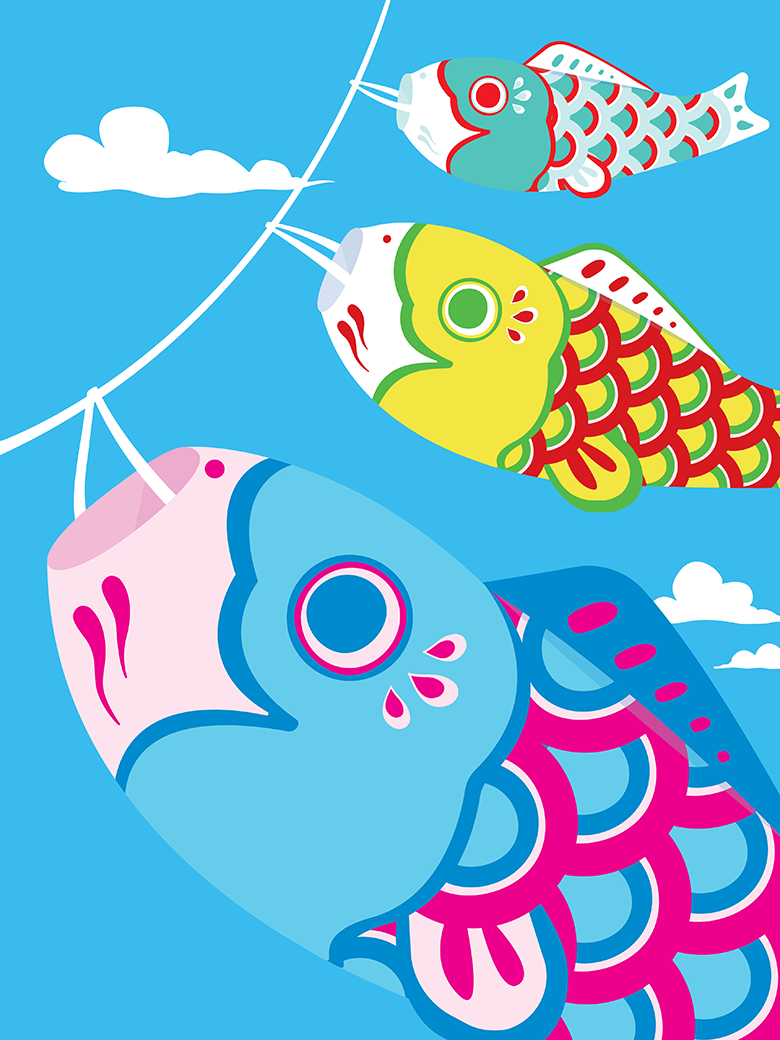

And with this, we would like to introduce you to the newest edition of our colourful Pop Art PICA print collection—the Koinobori (鯉のぼり) print. The print features the brightly illustrated koinobori banners floating amongst the bright blue sky's white clouds—a quintessential image of springtime Japan. Bearing our Pop Art colour and fun pattern design, the print hits that nostalgic note of warmth, sunshine and childlike innocence.

But what is koinobori? What does it have to do with springtime or Children's Day? Is there more to it than just being a colourful banner in the sky?

Beneath its colourfully painted scales lies deep symbolism born of an ancient legend, fearless warriors and history spanning hundreds of years across the land and sea. So let's start at the top: Children's Day.

Children's Day: The Origin Story

Children's Day or 子供の日 (kodomo no hi) takes place on May 5th and marks the end of the Golden Week in Japan, consisting of Showa Day (昭和の日, Shouwa no hi) on April 29th, Constitution Day (憲法記念日, kenpou kinenbi) on May 3rd and Greenery Day (みどりの日, midori no hi) on May 4th.

Children's Day holiday originated as Tango no Sekku (端午の節句). It is one of the five seasonal celebrations, Gosekku (五節句), that the Japanese imperial court, which was heavily influenced by the Chinese customs at the time, adapted from China during the Nara period (奈良時代, Nara jidai; 710 to 794). The Chinese-origin holiday is known as Double Fifth in China or as the Dragon Boat Festival in the West. Similarly, it falls on the fifth day of the fifth month. But unlike Japan, which has now adopted the Georgian calendar, the Dragon Boat Festival uses the lunar calendar. So unlike Children's Day in Japan, Double Fifth falls somewhere in June, with the actual date varying year to year.

All five adapted Gosekku holidays are still celebrated to this day. Just as Tango no Sekku is now known as Children's Day, so do the other ones now go by their alternative names.

Jinjitsu no Sekku (人日の節句), which originated in China on the seventh day of the first month, is now being celebrated on January 7th according to the solar calendar. In ancient China, each day of the first week of the Lunar New Year celebrations was dedicated to one animal that was forbidden to kill. The first day was dedicated to the chicken. The second to the dog. The third to the boar or pig. The fourth to the sheep, followed by the cow and the sixth to the horse. On the seventh day, known as human day, no punishments were handed to the criminals. As it got brought over to Japan, it became known as Nanakusa no Sekku (七草の節句, the feast of seven herbs) when it became customary to eat a seven-herb rice porridge (七草粥, nanakusa-gayu) to pray for health in the new year.

Then there is the March 3rd Joushi no Sekku (上巳の節句) that was adapted as Momo no Sekku (桃の節句, peach festival), also known as Hina Matsuri (雛祭り, doll festival), traditionally dedicated to girls.

It is then followed by the May 5th Tango no Sekku, Children's Day, and Shichiseki no Sekku (七夕の節句), adapted as Tanabata (七夕) or Star Festival (星祭り, hoshi matsuri) in Japan. And finally, September 9th Chouyou no Sekku (重陽の節句), adapted as Kiku no Sekku (菊の節句, chrysanthemum festival), where one drinks chrysanthemum sake to wish for longevity of one's life.

Now that we are familiar with the Gosekku holiday lineup, let's get back to the Tango no Sekku or as it is otherwise known as Shoubu no Sekki (菖蒲の節句, iris festival) or better yet as Boys' Day.

In China, the fifth month has long been considered unlucky, but the Japanese court chose to offset its negative association by celebrating it during the Nara period. The May 5th Iris Festival came from the tradition of drinking medicinal liquor with immersed iris plants and taking iris-infused baths to ward off evil and illnesses. Celebrating May 5th as Boys' Day, along with its modern-day traditions, became more commonplace during the Kamakura period (鎌倉時代, Kamakura jidai, 1185–1333)—a time when the samurai (侍), the warrior caste, emerged and thus established feudal Japan.

The word iris (菖蒲, shoubu) and its homonym for victory (勝負, shoubu) became interconnected with the iris flower becoming an essential emblem of the warrior class, and the Iris Festival became dedicated solely to celebrate boys' strength, ability and success. It became popular to decorate the home with samurai helmets, such as kabuto (兜) and koinobori.

During the Meiji era (明治時代, Meiji jidai, from 1868 through 1912), however, as a part of modernization on January 1st, 1873, the government adopted the Georgian calendar, and on January 4th of the same year, it abolished the five seasonal lunar calendar holidays, Gosekku. In communities, however, the Gosekku celebrations continued, and in 1948, one of them, the Tango no Sekku, due to its association with the Boys' Day, was renamed as Children's Day to celebrate the health and growth of both boys and girls and was made an official national holiday. The rest of the Gosekku celebrations continue to be celebrated, but are not considered to be national holidays.

Children's Day Decorations

The modern decoration practice can be linked back to the samurai's Kamakura period, when people began celebrating Tango no Sekku as Boys' Day. As a wish for their sons to grow up healthy and as strong as the samurai, households would display warrior dolls, samurai armour (鎧, yoroi) or samurai helmets (兜, kabuto) inside the home and hang koinobori (carp streamers) outside. While some households still display miniature samurai armour or samurai dolls today, it is koinobori decor that is most recognized and synonymous with Children's Day.

Let's take a look at the incredible world of koinobori.

Koinobori (鯉のぼり) in Japanese is a combination of two words, koi and nobori. Koi (鯉) is a carp, and nobori (のぼり) is a flag, a banner or a streamer. As the name suggests, koinobori is a streamer or a windsock dressed to resemble a carp. It is often meant to be flown in high places, such as one's balcony, children's park or school grounds. It can be as small as a miniature and as large as one can imagine. The largest one, for instance, in Kazo, Saitama, where the streamers are actively produced, in 1988 reached up to 100 meters in length! These streamers adorn the landscape of Japan beginning in April through early May. The sight of the carp streamers dancing in the wind makes it seem as if they are truly swimming in the blue waters of the sky.

But how did the carp on the nobori banners come to be?

The first koinobori with painted carp imagery came to be during the Edo period (江戸時代, Edo jidai, 1603 to 1868). They were heavily influenced by the nobori flags used by the samurai of the Sengoku period (戦国時代, Sengoku jidai, "Warring States period," 1467 to 1615) on the battlefield. While the use of a windsock came to be related to the samurai, the carp was born out of a legend.

The Carp and the Legend

The Tango no Sekku originated in ancient China. And so did the legend of the carp. As the legend goes, a school of fish was swimming against the river current as it approached the waterfall, known as the dragon gate (龍門 or 竜門, ryuumon). While most fish gave up, the carp proceeded to swim up the waterfall and was brave enough to leap over it. As it leaped over the gate, it transformed into a mighty dragon. The Chinese dragon's discernible scales remind us of its being a descendant of the carp. It is a powerful, benevolent creature and an auspicious symbol since ancient times. Its existence is a cultural symbol of bravery, perseverance and success.

There is even a Chinese proverb "鯉魚跳龍門" (lǐyú tiào lóngmén), which translates to "The carp has leaped through the dragon's gate." It represents the ability to overcome obstacles and to succeed. And as they rise in the sky, the koinobori streamers embody parents' desire for their children to grow up strong and successful.

Chinese dragon in a temple in Sapporo. Photo by Alyona Polianskaia

The Koinobori Look

When the koinobori were first seen during the Edo period, they were only painted black to resemble the wild carp's colour. Over time in Meiji and then the Showa periods, colours like red and blue began to be introduced. Until recently, the "traditional" koinobori tended to use specific colours and be hung in a very particular order.

Today, it would be difficult to spot a complete traditional set in an urban setting. Due to limited space and small balconies, people opt for a miniature indoor display set or a couple of koinobori streamers hung on the window.

The koinobori are no longer only hung vertically on the pole as they did back in the day. These days, they are more often hung horizontally across. This practice is especially popular with public displays of koinobori, where tens or hundreds can be hung up in vast open spaces like fields, rivers and lakes for public events and festival celebrations.

The standard koinobori set consisted of a large black carp (真鯉, magoi) representing the father, followed by a smaller red carp (緋鯉, higoi) representing the mother, and lastly by an even smaller blue carp representing the eldest son. Additional smaller carps in remaining colours, such as green, orange and purple, would follow to represent the younger siblings, originally sons.

The carp family set, established during the Showa period, would be displayed by attaching each streamer to a pole in order. The first koinobori from the top would be the black 'father' carp. It would then be followed by the 'mother' carp and the 'children' down below. Above the 'father' carp, a pair of moving arrow-spoked wheels 矢車 (yaguruma), a decorative windmill, would be attached to the top of a pole. Along with it would be placed a golden round spinning vane called 回転球 (kaitenkyuu) and 吹き流し (fukinagashi) colourful windsock streamer often adorned with the family crest. All of these were meant as a form of protection from harm and against evil.

Nowadays, the streamers also come in various sizes, including small ones for indoor use and in a large variety of colours and fun, creative patterns that have a fresh, modern feel to them. They are also no longer exclusive to boys, and many families hang koinobori to honour all of their children.

So when should you see the koinobori soar in the sky?

The koinobori can be seen as early as the last week of March, following the Spring (Vernal) Equinox (春分の日, shunbun no hi) national holiday, and up until the middle of May, after the Children's Day celebration comes to an end. Some households choose to keep the koinobori up until June to honour the original date of the 5th day of the 5th month as per the lunar calendar.

As with everything in Japan, objects on display tend to have an auspicious meaning attached to them. Koinobori is no exception to this rule. People proudly hang the streamers as a wish to attract fortune and good luck to the children. The carp symbolizes strength, health and perseverance. And with koinobori, the parents wish their children to grow up strong, healthy and successful in life. The holiday is no longer exclusive to the boys in the family but has evolved to include all children regardless of gender.

With our PICA Koinobori Pop Art print, we wish to share this wonderful cultural icon with you. These colourful koinobori represent childhood, innocence, spring, warmth, celebration, strength, achievement, prosperity and growth. Hang the print on your wall to stay in touch with your inner childhood ambitions. Frame it in your kids' room as a wish for them to grow up as the magical, mighty, soon-to-become-dragon earnest carp.